A Guarantor Bubble?

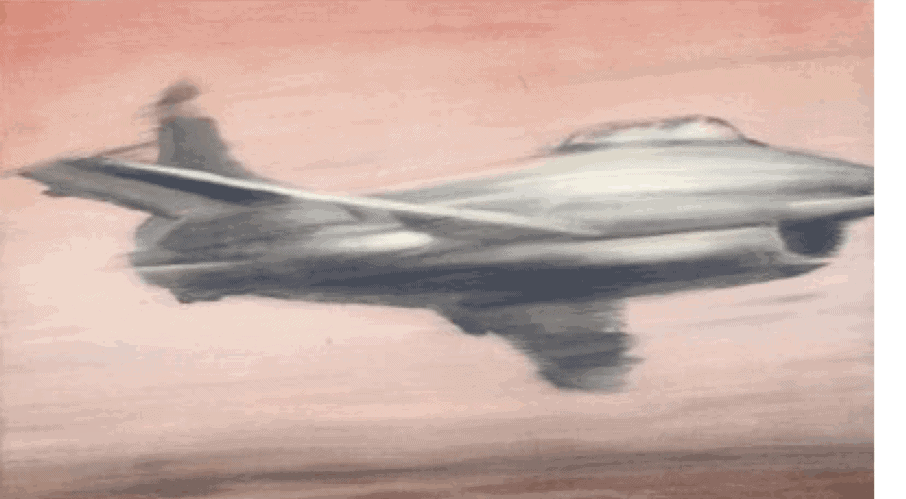

How can a Gerhard Richter lose 50% of its value in only 3 years? The artwork Düsenjäger (1963) has become symbolic of the trouble with auction houses’ reliance on guarantees and the market distortions that they entail. Not only do they manipulate the value of works, and by extension the market; but they are also becoming a liability to auction houses.

The Art Market Monitor reported that Gerhard Richter’s Düsenjäger (1963) is back on the market, this time with auction house Phillips. The work has been mired in a legal quagmire ever since its sale at Christie’s in November of 2016.[1] Estimated between 25,000,000 – 35,000,000 USD, the artwork failed to secure a bid and went to its third-party guarantor Zhang Chang for $24M. However, the collector refused to pay up since it does not appear he had the funds to make such a payment. On discovering that Mr. Chang was also the successful buyer of a Francis Bacon diptych at a Christie’s auction in 2015, Phillips convinced a judge to attach this Bacon to the lawsuit as collateral towards the outstanding payment. Unfortunately, Mr. Chang doesn’t properly own “Study for Head of Isabel Rawsthorne and George Dyer” (1967) neither, since he still owes a £12.1 million loan to Mr. Lin San. Now, in order to clear cascade of lawsuits, the work is back on the market with a £10-15 estimate –the same price that it was auctioned in 2007. [2]

This heavy discount is an example of how even the noblest idea can be distorted by greed. Guarantees were born out of the fact that if an artwork offered at auction fails to meet the undisclosed reserve price, the lot is thus “bought in” or “burned”. Consignors may have to wait up to 6 years to dilute the BI effect and place the artwork for auction again. Auction price guarantees resolve this problem essentially by issuing a form of insurance that removes risk from the consignor despite what may happen in the sales room. If a lot does not sell, the guarantor buys the artwork; if a lot sells below floor, the guarantor pays the difference; and if a lot sells above floor, the guarantor splits the overage. Additional guarantee issuance fees (i.e. “financing fees”) range between 3% to 5% of the guaranteed amount.

Auction houses use guarantees to help convince collectors to part with works at auction by mitigating no-sale risk though securing a minimum purchase price. In the cutthroat auction world in which houses compete to achieve record sales for trophy works, auction houses waiving sellers commission fees and use these minimum sale prices to secure top lots. Furthermore, guarantors seed the buyers pool, provoking other buyers with early interest helping to drive up hammer prices. [3]

To give a sense of the widespread use of this practice, in the Evening auctions of 2018, almost two-thirds of the sales were guaranteed. Art Tactic estimates that the combined value of the guarantees from Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips 2018 fall hails up to $537 million.[4]

The main problem with these anonymous guarantors is the asymmetry in the information between auctioneers and buyers. Despite auction houses are known for tilting in favor of a free and transparent market, the truth is that this anonymous practice sets a disadvantage to the buyer by ignoring the amount of a pre-sold lot. Moreover, the consignor is also in a drawback, since he needs to pay an extra fee to secure the sale of their artwork. Instead, auction houses should improve their effort to find new reputable collectors and selecting better quality lots.

Beyond the distorting effect on the market and their prices, guarantees distort the value of works and expose the art market to manipulations, bubbles, and fraud, as in the case of Mr. Chang. This is why Artemundi prefers using private transactions to avoid auction risks and provide better returns for non-performing assets.

During next week’s sale of Gerhard Richter’s Düsenjäger (1963), the buyer (or guarantor) will not only take home an important work in art history, but they will also take home an important bellwether in art market history.

[1] Maneker, Marion. “Phillips London Contemporary Has Richter, Kippenberger and Lichtenstein.” Art Market Monitor, 20 Feb. 2019, www.artmarketmonitor.com/2019/02/20/phillips-london-contemporary-has-richter-kippenberger-and-lichtenstein/.

[2] Kaplan, Isaac. “$24 Million Richter and $15 Million Bacon Embroiled in Nonpayment Dispute.” 11 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy, Artsy, 17 Aug. 2017, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-24-million-richter-15-million-bacon-embroiled-nonpayment-dispute.

[3] Woodham, Doug. “The Trick Auction Houses Use to Get Collectors to Sell Their Art.” 11 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy, Artsy, 28 June 2018, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-guarantees-good-art-market.

[4] “Price Guarantees Are Common at Art Auctions.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, 13 Dec. 2018, www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2018/12/15/price-guarantees-are-common-at-art-auctions.