Amongst Volcanos with Dr. Atl

Visionary and fantasist, teacher and mentor, poet and novelist, journalist and publisher, city planner and utopian dreamer; many adjectives can describe the multifaceted personality of Dr. Atl. Nevertheless, he mainly remains as one of the most internationally recognized Mexican nationalist painters. The Guadalajara-born artist signaled his admiration for Mexico’s culture by changing his name, around 1900, from Gerardo Murillo to the word “Atl” which means “water” in the native American Nahuatl language spoken by the Mexicas or Aztecs. Educated in Mexico City, Rome and Peru, he founded the journal Action d’art in Paris in 1913 and edited it for three years. After two prolonged stays in Paris and Rome (1896 – 1903 and 1911-14), he returned to Mexico with firsthand knowledge of the trends in European art, such as Neo-Impressionism and Futurism, both of which are reflected in his own work.

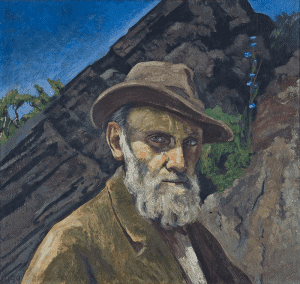

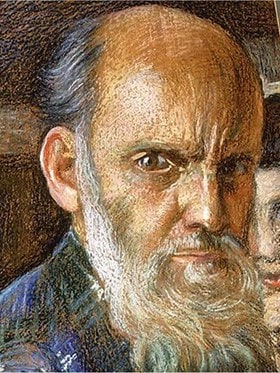

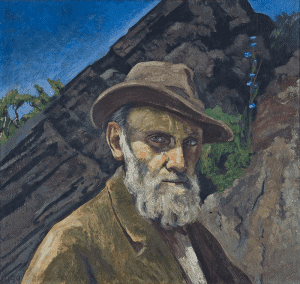

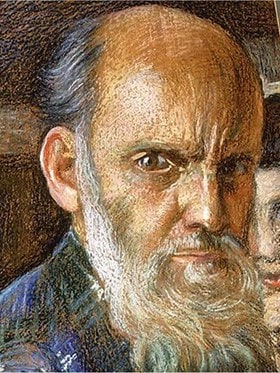

Atl’s artistic production was influenced by the Impressionists’ palette and the audacious plastic technique of the members of the School of Paris, especially that of Toulouse Lautrec.[1] This can be noticed in Self-portrait (1949), which is composed of several strata that achieve different tonalities and brushstrokes. As we can see in this artwork, Dr. Atl not only used a pointillist effect but also his famous “Atl Colors”.

Gerardo Murillo experimented with different styles, compositions (including aerial), and curved perspectives. He produced intense works with unique color profusion. He also tested diverse supports and mixes of materials. Although some of the results were at times adverse, there were also successes. Due to his experience with pastel and frescoes, he felt compelled to seek out less limiting supports. Around 1915, he invented a color bar that could be applied cold and that allowed for sufficient time to dry. He called it “Atl Color”. It was an encaustic made of wax and pigment but also resins, which helped achieve innovative effects.

Dr. Atl painted many self-portraits. The one created in 1949 typifies the way in which he fashioned his own image, which was inextricably linked to the volcanic Mexican landscape that he studied and loved for most of his life. The veracity of his physical image and his own projection were of great importance to him, and thus he reinvented his physiognomy and gestures according to his age and mood. His voluminous beard, intense gaze and severe posture reveal the artist’s stern personality. Interestingly, 80% of his self-portraits were created after the 1930s, when he was about 55 years of age. His egocentric desire of legacy and acknowledgment, fortunately, left a rich series of mature -and skillful- self-portraits.

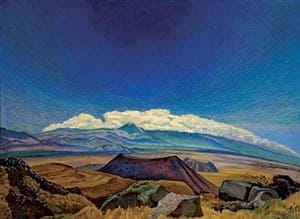

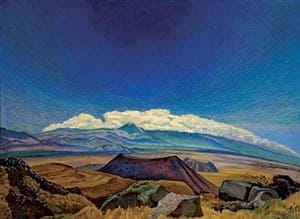

Unlike familiar self-portraits by Rembrandt, Goya, Picasso, or Frida Kahlo, among many others, in the 1949’s Self-portrait, Atl chooses not to set his image within his studio but he paints himself in front of a highly dominating volcanic background. This type of composition, common to Murillo’s portraits of himself, reveal Atl’s devotion for depicting the countryside, which according to some experts, requires great inspiration, deep comprehension of nature, simplification of form, styling, unity and extraordinary technique.[2] “Unlike landscape artists who preceded him, Atl didn’t reproduce the topography. Rather, he painted the sensations he felt when he was immersed in the landscape.”[3]

He was passionately interested in Mexican scenery and the creation of an indigenous but modern artistic style of expression. The multi-faceted and controversial Gerardo Murillo truly loved Mexico’s countryside, especially its volcanoes. The self-titled “volcanologist” would get so close to them, literally and metaphorically, that his works seem to channel their force. In his paintings, viewers see scenes they would only witness by being amidst lava, clouds, ashes or snow. Atl applied the Impressionist plastic method in the tradition initiated by artists such as Egerton, Landesio, José María Velasco and Luis Coto. The artist recalls in his manifest: “Landscape has needed centuries in order to achieve the evolutional degree of power, perfection and emotional strength.”[4] By rescuing this category, combined with a modern approach, Atl endowed his art with a new meaning of nationality and cultural memory. That is to say, Dr. Atl managed to portray the fortitude and character of the first decades of twentieth-century Mexico through his style, while exalting the pride of the land and showcasing the country’s beauty and grandeur. He also applied the curved horizon perspective created by Luis Serrano, which enriched the explosion of color and superposition of visual layers in his technique. Such chromatic qualities turned his landscapes and self-portraits into living entities that cause a sentimental reaction and reveal the nature of the deep emotions of the artist.

As a committed political and social activist in the early decades of the twentieth century, Atl not only produced a great body of work but also brought real change with him. He led the initial efforts to secure government-sponsored mural commissions for Mexico’s artists in 1910 and he received one of the first such commissions from education secretary José Vasconcelos in 1921.[5] Murillo, in fact, was involved closely in politics between 1910 and 1928. Throughout his lifetime, the artist retained the friendship and esteem of many of the most prominent figures in Mexican arts and letters, including José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, the three great Mexican muralists whose emerging talents he nurtured. He died in 1964 and is buried in the “Rotonda de Los Hombres Ilustres” in the heart of Mexico City.

[1] Dr. Atl. Masterpieces, Exhibition catalogue, Museo Colección Blaisten, México City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 2012. p. 13

[2] Ibid. p. 136

[3] Ibid. p. 9

[4] Please refer to the Spanish version at: Luna, Antonio. El Dr. Atl, Sinopsis de su vida y su pintura. Mexico, D.F: Editorial Cvltura, 1952. p. 135

[5] Please refer to the Spanish version at: Hernández, Marisa. Reflejos del Paisaje Mexicano. Mexico City, Mexico: Lindero Ediciones, 2009. Print. p. 46