Art Needs Truth, Not Sincerity

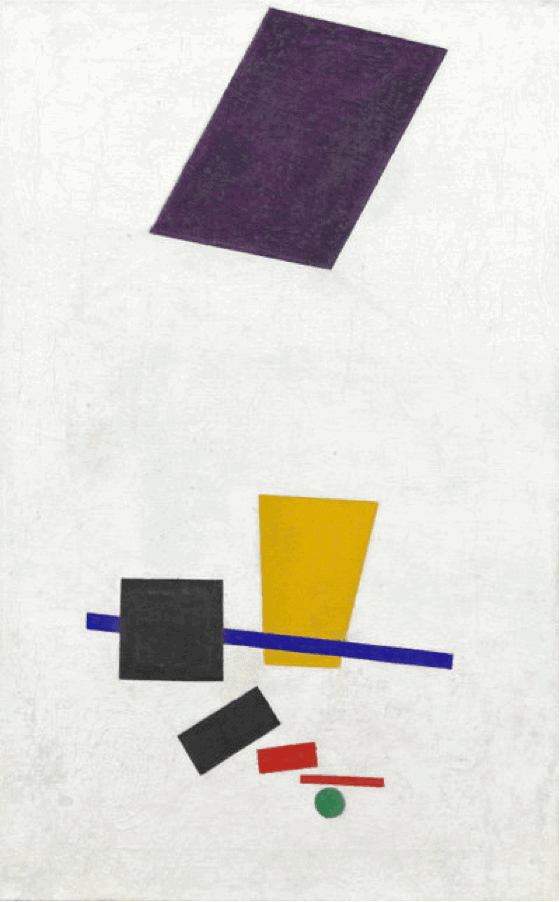

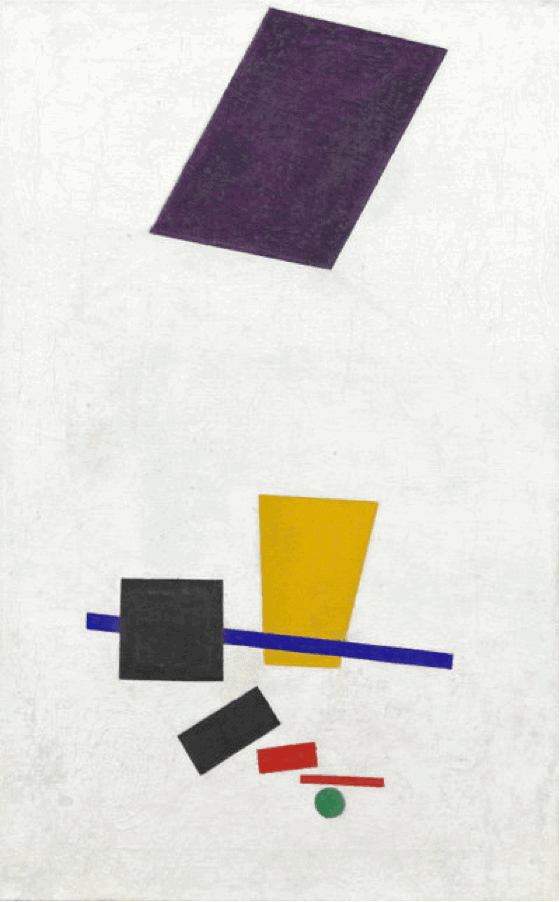

These famous words by Kasimir Malevich in the Suprematism Manifesto should resonate once again among the art market leaders under the following key differentiator:

Truth is a property of an utterance, whether or not it corresponds with objective (or sometimes subjective) reality.

Sincerity is a property of a person/company communicating, whether or not they believe in the truth of what they’re saying.

When layering these words to the current unregulated and arguably corrupt art businesses, we realize that provenance continues to be an essential dilemma that intoxicates the marketplace where lineage is stained by half-truths.

As advocates of transparency, we have always promoted measures such as due-diligence, UBO, and KYC in each of our transactions. While our partners and associates have slowly but positively embraced these practices, the case of provenance remains hidden under murky waters.

The Importance

The term “provenance” first entered the English language in 1785 to describe any antecedent of the painting. It was after 200 years when it was rekindled in the 1926 publication of the Oxford English Dictionary as: “The history or pedigree of a work of art, manuscript, rare book, etc.; a record of the ultimate derivation and passage of an item through its various owners.”[1]

Most recently, the archetypical lawyer’s narrative has questioned the exercise of the term and its broad spectrum of rights and connotations. For example, legal ownership does not necessarily mean physical possession and vice versa. That is to say, the person who has the physical custody of the painting, well may not be the legal owner of that artwork. And possession, whilst available as evidence to support a claim to ownership, does not determine ownership by itself.

An early case in the importance of provenance was the notable sale of the collection of King Charles I. Following the tumultuous English Civil War in 1649, the English Parliament embarked on the brain-draining task of inventorying, valuing, and selling the royal art collection. This sale is considered as the oldest well-recorded event where the social and historical circumstances became inextricably linked to the artwork’s reputation and consequently, its appreciation. More than 35,000 paintings were dispersed into private hands during the sale and then expensively retrieved by Charles II after the restoration of the monarchy, making the decade of 1690’s one of the busiest art markets in Europe.[2] The knowledge that art was valuable, readily sealable, easily transportable, and often profitable became widespread, boosting provenance’s critical importance when engaging in high-valuable transactions.

Nowadays, we continue with that legacy, since items owned by Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe of John F. Kennedy have sold for tremendous amounts of money. In 1998, Sotheby’s sold a cookie jar owned by Andy Warhol for $247,830,[3] the equivalent of $396,715 in today’s US dollars.

Apart from the financial benefits of having full-enhanced lineage, provenance research is central when authenticating a work of art. For over 50 years, institutions such as the IFAR, have recognized from the outset that in-depth provenance research, along with connoisseurship and the study of the material properties of a work of art, is key to verify its authenticity. The provenance also determines whether a possessor can legally own an artwork or whether the original owner can effectively execute his/her ownership rights to sell. The location of an object at a particular point in time may also establish which cultural heritage or patrimony laws if any, apply. Therefore, provenance information is fundamental to initiate a lawsuit or demand for restitution.

Finally, on a broader sociological dimension, knowing the names of collectors and benefactors enables scholars and sellers to analyze the underlying structures of economic and cultural power that influence the when, who, and which artists become inscribed in the history of art.

The Challenges

However, not everyone agrees with these obvious remunerations of transparent provenance. Unlike many other economic systems, the art market lacks effective national and international regulatory agencies to manage the behavior of its actors through the softer inducements of trust, reputation, and endorsement. Inside this unique environment of self-approbation, transactions are often conducted through verbal agreements or without a written contract. This practice leads to an asymmetry of knowledge, where information becomes currency and knowledge disparity can lead to widening margins between a purchase and a resale price.

Dealers and auction-house specialists occupy a privileged position as gatekeepers of such information, as they are often aware of the identity of the consignor and the sales history of a specific object, but their consignments are often conditioned to exclude the information deliberately or erroneously to secure the deal. Confidentiality agreements may be imposed as conditions of consignment or various legal and tax motivations prevent full disclosure of information. Even money laundering and Nazi-looted cases can arise from the lack of transparency within the provenance. Complex cases of looted artworks in prominent collections have surely put the spotlight on what a lack of transparency within the provenance can provoke.

Even without intentional dissimulation, mistakes are frequent and are often compounded when repeated from publication to publication. Collector’s names are misspelled, foreign titles get mistranslated, incorrect owners’ names get attached or concealed; dealers may be mentioned instead of owners, or similar titles get confused depending on the interest of the seller; all of which muddies the ownership chain and at times, also prove the authenticity of an artwork.

As the years go by, information and evidence on provenance knowledge recede, can get lost or become obscured. And the answers tend to appear if at all, scratched or seen through a distorting glass.

Our Approach

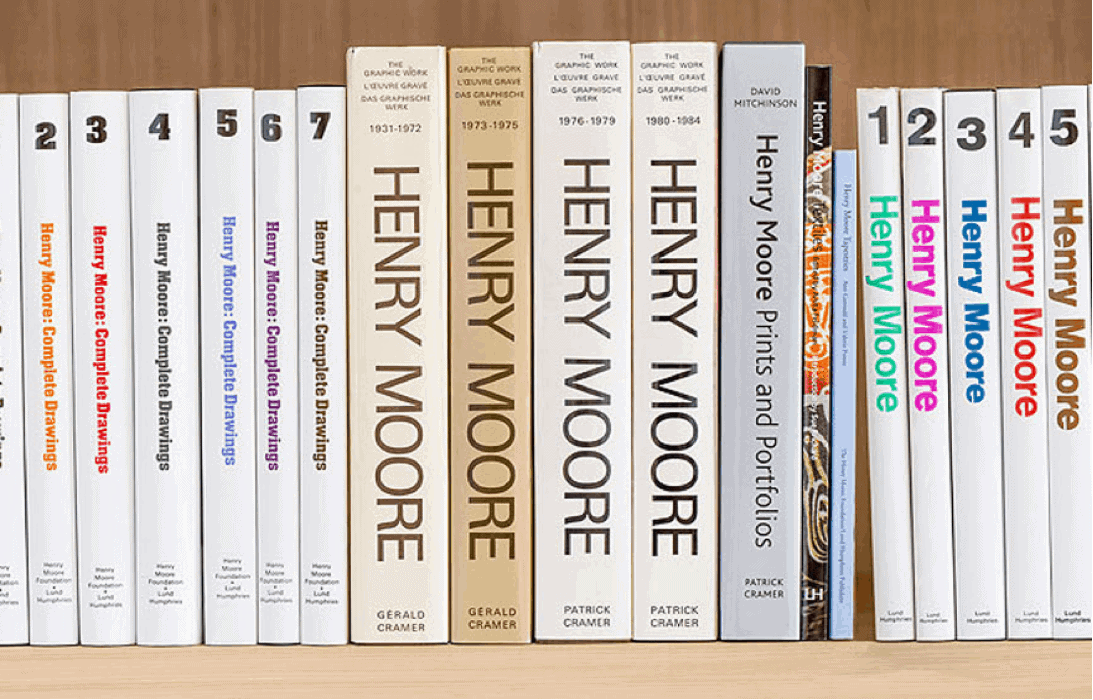

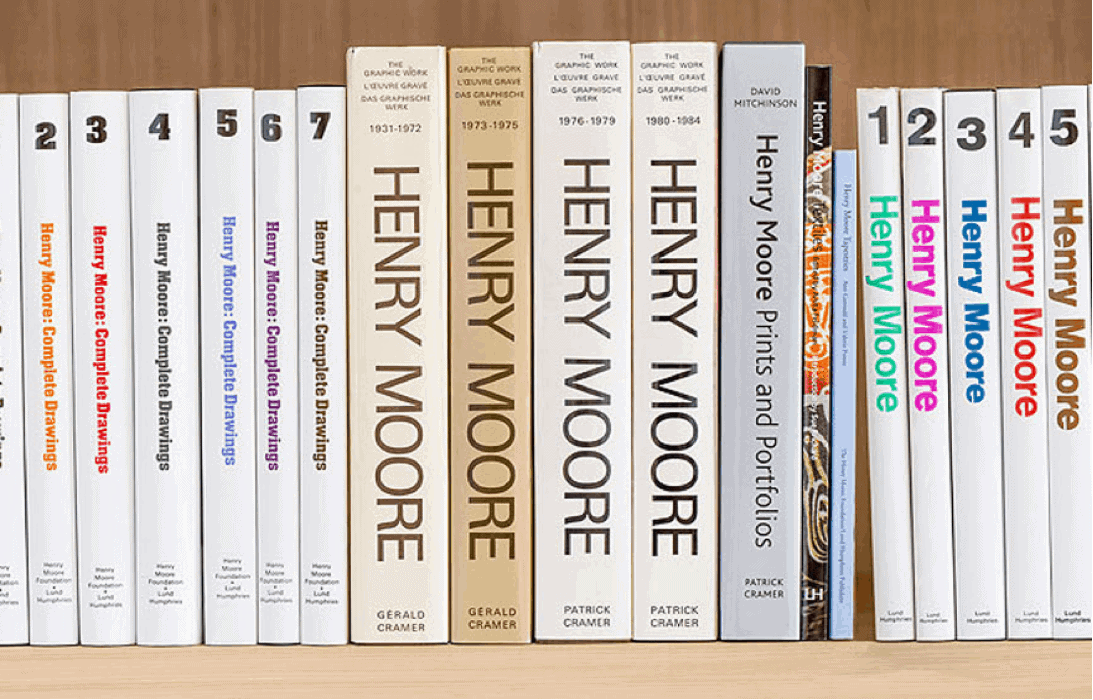

Throughout our 32 years in the business, we have learned to have systematic attention to detail and apply a tripartite non-exclusive approach with (1) connoisseurship: the ineffable expert judgment built on experience, exposure, instinct, feeling and art-historical awareness; (2) boards or committees: often established by the artist’s state, and empowered to deliver final judgment on the attribution of a work and withhold the artist’s cannon; and (3) catalogues raisonnés: purportedly comprehensive listings of all works by a given artist in an identified medium.[4]

Most recently, the advancements in technology and the development of databases such as Artnet or The Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance (PSCP) from the Getty Research Institute, have already had an impact on the provenance research field in terms of generating wider, quicker and more cost-efficient access to digitized material, making it possible to search across extensive pools of data to answer important questions more efficiently.

Since we often work with best-in-kind dealers who are used to maintain anonymity to protect the transaction, we have placed in place the signature of Non-Circumvention Agreements. Through this practice, our sellers and intermediaries can feel comfortable that their commissions and position within the transaction will be unconditionally respected.

However, auction houses, galleries, and dealers should be legally obliged to disclose the real and complete provenance information in their catalogues, as they often conceal the name of the last consignment. And ultimately, it is their responsibility to orchestrate the transaction with transparency and due-diligence.

We can only hope that more and more art market sectors keep embracing our transparency ideals and embrace clearer provenance practices to secure each artwork’s place in the continuing story of art.

[1] Tompkins, Arthur. “The History and Purposes of Provenance Research” in Provenance Research Today: Principles, Practice, Problems. London: IFAR & Lund Humphries, 2020, p. 16

[2] Tompkins, Arthur. “The History and Purposes of Provenance Research” in Provenance Research Today: Principles, Practice, Problems. London: IFAR & Lund Humphries, 2020, p. 18

[3] Times, The New York. “Warhol Cookie Jars Sell for $247,830.” The New York Times, 25 Apr. 1988, www.nytimes.com/1988/04/25/arts/warhol-cookie-jars-sell-for-247830.html

[4] Flescher, Sharon. “The Challenges of Provenance Research” in Provenance Research Today: Principles, Practice, Problems. London: IFAR & Lund Humphries, 2020, p. 39