Bauhaus Centenary: 100 Years of Rethinking the World through the Eyes of Josef Albers

To distribute material possessions

is to divide them,

to distribute spiritual possessions

is to multiply them.

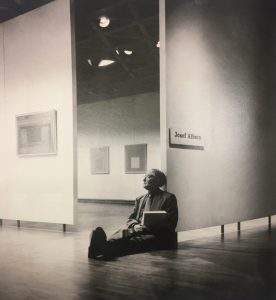

The Bauhaus, the most influential art and design school in history, celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2019. This overview will highlight the perspective of Josef Albers and his artistic legacy in the 21st century.

There are moments in history when a confluence of ideas, people, and broader cultural and technological forces creates a spark. Sometimes the spark amounts to nothing more than a flicker. But if conditions are right, it can erupt into a dazzling, brilliant light that, while burning for only a brief moment, changes the world around it. The Bauhaus was one of these – a place that despite the economic turmoil and cultural conservatism of the world around it, offered a truly radical, international and optimistic vision of the future.

No school of design has been as influential as the Bauhaus. Although the Bauhaus “style” has been commoditised, its most iconic works now available as reproductions and knock-offs, the radical zeal embodied in its ethos and output is still there.

It is easy to see the Bauhaus in black and white or in the bold primary colors of its typography, its subtler tones and narratives are harder to discern. So legendary is the school founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius, that its nuances can be missed.

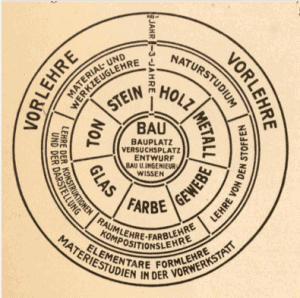

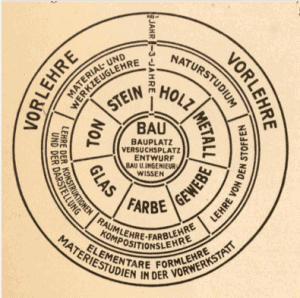

The Bauhaus was created as the combination of a college of fine arts and a school of applied arts. The goal of the Bauhaus is to bring the art training hitherto isolated from practical life into harmony with the actual demands of contemporary life. To this end, its integrated program of teaching theory and workshop activity which is to be performed in accordance with present-day technological industrial working methods.[1]

The new school was heralded confidently with jaunty oversized exclamation points and industrially produced utilitarian design. More than a utopian collective, the Bauhaus was a story of heady optimism and ambition.

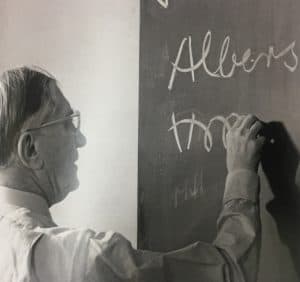

Despite we know how the story ends, the ideas, design, and art that emerged from the Bauhaus were to change the things around us, how we use them, and how they made us feel. This energy was transmitted and illustrated in two short paragraphs by Gropius when the school was first advertised in 1919. Something in it resonated deeply with Josef Albers, a son of a carpenter born in 1888 in Bottrop. He abandoned his plans to leave Germany, and enrolled as a student in the Bauhaus. Later Albers would say about this decision: “I was 32, I threw all the old junk overboard and went right back to the beginning again. It was the best thing I ever did in my life.”[2]

In 1920, when Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer joined the new school, they ignore how important the movement was to become, not what ruin awaited in Germany. Albers’s first constant home at the Bauhaus was the glass workshop. It was one of several others focusing on wall painting, ceramics, metalwork, and cabinet making and weaving.

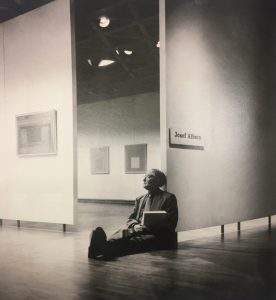

Arriving as a student, Albers would ultimately leave the Bauhaus thirteen years later, having taught there longer than anyone else. [3] Despite the infighting and competitiveness endemic in any academic institutions, the environment in the Bauhaus rewarded talent. Albers’s evident skill as an artist and craftsman resulted in him being commissioned to make stained glass windows for the outer room of Gropius’s office in 1922.[4]

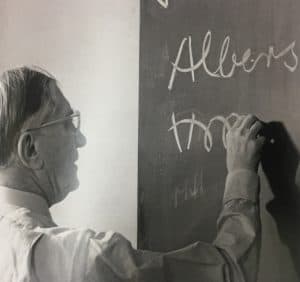

Albers would take an increasingly pivotal role as an educator at the Bauhaus, eventually becoming head of the preliminary course, a post he held until his departure. His characteristic practice and teaching commitments would become a testament to the school. His ethos would be in line with the spirit and aesthetic of the Bauhaus.

It was at the Bauhaus where Albers would mature as an artist and teacher. But perhaps Albers’s most important discovery at the Bauhaus was the young weaving student Anneliese Fleischmann (later Anni Albers).

Albers’s legacy beyond the Bauhaus

One of the most influential artists and theorists of the twentieth century, Albers drew on over forty years work in a variety of media –woodcuts, sandblasted glass pictures and oil paintings- for these rigorous yet lyrical explorations of colour and form, and they can be seen as the summation of his creative life.

A famed coiner of aphorisms, Albers often repeated that among his aims in art and in life was that of achieving the “maximum effect” through “minimal means”. [5] For Albers, this is translated into the use of a few straight lines as possible to create rich spatial events, the skillful manipulation of an engineer’s tools to invoke mysterious forms that appear and disappear before your eyes, the most refined arrangement of flat squares of unformulated color to give birth to an alchemical process whereby illusory shading, color penetration, after-image, and a spectral glow all occur.[6]

Deeply interested in mastering crafts and manual skills, for him, art was a perfectly balanced equation between effort and effect. In a reflexive manner, he applied this austere sense of artistic practice to his theoretical essays, educational texts, teaching, the design of furniture and objects, typography, photography and painting.[7]

Albers used to teach all of this in his preliminary course at the Bauhaus. Whether they were to become architects or painters or sculptures or industrial designers, all the students had to take this course in fundamental design.

Through his art, and his teaching at Black Mountain College and at Yale University, he influenced generations of artists, including Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Rauschenberg and the exponents of Op art.

The following abstracts from a letter by Wassily Kandinsky and a poem by Hans Arp express the deep appreciation each student and colleague would refer to Josef Albers:

His pedagogical activity is one of the best memories I retain from the school, which unfortunately exists no more. There, he gave the whole measure of his inventive strength and his vivacity, the strict structure of his method was so impressive that he soon found imitators among teachers and other German universities.

Many of my friends and their pictures no longer want to be here.

They want to go to the devil.

How one longs in their presence for an Albers.

The world that Albers creates carries in its hear

The inner weight of the fulfilled man.

To be blessed we have to have faith.

This holds also for art and above all for the art of our time.

All the qualities from Arp and Kandinsky quotes – from balance to unity – exist in Josef Albers’s work. Furthermore, they also pertain to the conduct of his life. His Homages to the Squares are infused by his discipline, strength and fiery passion harnessed by resilience and order. These values are much needed in our 21st century day life and should be resumed back into our lives.

Although the Bauhaus lasted little more than a decade, a simple measure of its significance is that no school of architecture or design can legitimately claim not to have been influenced by it in some way. But the Bauhaus’ impact extended far beyond design education – it was a place conceived from the beginning to grapple with a fast-changing world, and to find a cultural response that would not just mitigate its transformations, but to mold them for the benefit of all.

In this increasingly reactionary and populist world, the ideals of the Bauhaus – its internationalism, its willingness to grapple with, rather shy away from, a changing world, and its fundamental optimism about the future – are needed more than ever. This is why we are proud to hold with deep esteem an outstanding collection of Josef Albers’s artworks waiting for a collector who is willing to respond to this call.

[1] Bauhaus Weimar. Hamburg: Kraus Reprint1980., 1980. Print.

[2] Albers, Josef, and Oscar Humphries. Albers & the Bauhaus. , 2016. Print. p. 5

[3] Albers, Josef, and Oscar Humphries. Albers & the Bauhaus. , 2016. Print. p. 7

[4] Ibid p.8

[5] Albers, Josef. Josef Albers: Minimal Means, Maximum Effect: March 28-July 6, 2014, Fundación Juan March. Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 2014. Print. p. 13Bottom of Form

[6] Albers mimimal effect p. 15

[7] Albers mimimal effect p. 13