Money often costs too much: The moral obligation to ethical sources of institutional funding

“Money often costs too much”, Ralph Waldo Emerson could have meant many things with this quote, but it is important to stop once in a while and think what are we sacrificing for money? Today’s conversation merely serves as a timely reminder of the degree to which museums and cultural institutions must look outside of traditional forms of fundraising to meet their operational costs. It’s clear then that new models are needed, and a number of institutions are presenting interesting case studies.

Grants, galas, gifts, and auctions remain the standard sources of income for arts organizations looking to meet operational expenses left uncovered by earned income or endowment interest. However, according to a study by SMU Data Arts, from 2014-2017 these fundraising activities have shown a 20% industry-wide decrease in return on investment for large and mid-size organizations, most notably among art museums[1]. Beyond this downward trend, the persistent problem is that these sources of funding are inherently unreliable. This unpredictability represents an operational difficulty for organizations as it complicates future programming projections and their ability to recruit top talent.

Furthermore, the fact remains that cultivating major donors is challenging. Museums invest years and significant sums to build relationships in the hopes of cultivating future significant donations, yet the occurrence of pledged gifts going unfulfilled by donors or their heirs is common.

Cultural philanthropy is a valuable and common strategy for corporations to burnish unsavory reputations. As steward of public interest, public institutions, in particular, must carefully weigh the decisions of whom to align themselves with vis a vis their funding.[2] In some cases, the moral imperative for ensuring ethically sounds donations is even reflected in public policy. The UK, for example, prohibits cigarette companies from sponsoring sporting and cultural events with the brand names of their cigarettes.[3] Yet as museums face rising operating costs and aging infrastructure in need of updating, it can be hard to sever ties with major donors.

These sustainability challenges are all the more heightened for private museums who depend on a single founder’s vision and pocketbook for support. Though established with the best of intentions, all too often founders are caught surprised by the high costs of maintaining a museum. In China for example, which leads the world in a number of private museums, the 2019 TEFAF report on the Chinese art market revealed that without a public policy in place to support cultural philanthropy, such as western-style tax incentives, Chinese private museums have approximately 10 years of capital remaining. In Los Angeles, the Main Museum’s recent sudden shuttering[4] was an example of an institution that was simply unprepared for the high cost of running an arts space.

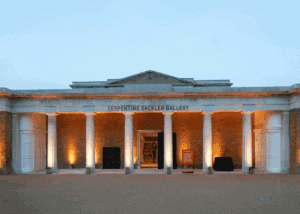

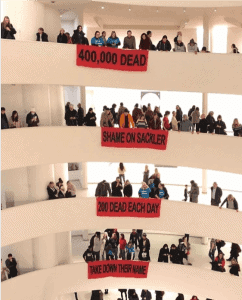

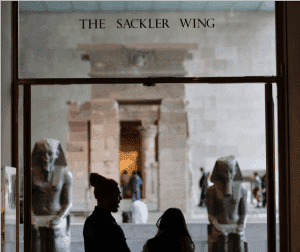

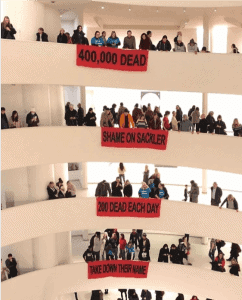

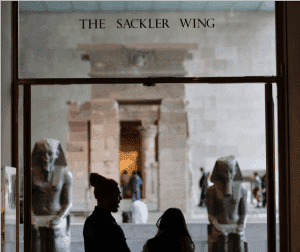

The growing list of museums publicly severing ties with the Sackler Trust, the philanthropical foundation funded by the Sackler family, makers of the opioid OxyContin, has reignited the public debate about the moral imperative of museums to reject major gifts of funds from ethically dubious origins. The list of cultural institutions and initiatives founded by the Sackler Family includes important institutions such as: Dia Art Foundation’s Sackler Institute, New York; Guggenheim Museum’s Sackler Center for Arts Education, New York; Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Sackler Wing, New York; British Museum’s Raymond and Beverly Sackler Rooms, London; National Gallery‘s Sackler Room, London; Royal Ballet School, London (funded by the Sackler Trust); Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew’s Sackler Crossing, Richmond, UK; Royal College of Art‘s Sackler Building, London; Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London; Shakespeare’s Globe’s Sackler Studios, London; Tate Modern‘s Sackler Escalator, London; Victoria and Albert Museum‘s Sackler Courtyard, London; Louvre’s Sackler Wing of Oriental Antiquities, Paris; and the Jewish Museum Berlin‘s Sackler Staircase, Germany.

Last week, New York City and The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently announced that the $2.8M dollars that the Met has generated in earned income from implementing a $25 admission for out of state visitors will be distributed to 175 arts organizations in the city with a particular focus on arts organizations in “underserved communities”[5]. This redistribution model is also reflected in the commercial sphere at fairs like Art Basel which are experimenting with a tiered pricing system, by which larger galleries effectively subsidize the booths of smaller and midsized galleries with the philosophy that more diverse participation benefits everyone by making the fair generally more interesting.

Meanwhile, LACMA has just announced a radical new merger with the Yuz Museum, a private museum in Shanghai, which has the potential to shape international relations between museums as well as foreign public policy[6]. This highly unusual legacy plan by founder Budi Tek assures an institutional future for the Yuz, allowing it to continue to operate locally while benefiting from LACMA’s institutional resources and experience. Perhaps more crucially, however, this merger gives LACMA a local foothold through the Yuz’s reputation in Shanghai, essentially exposing LACMA as “hero brand” to a group of local donors who are motivated to institute a non-governmental multi-donor museum patronage system in China.

Sustainability strategies do not have to be as politically ambitious as the Met or LACMA’s. Some museums are looking to their storage facilities with the realization that their contents represent both a significant cost as well as cash-flow opportunity[7] At the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, a $14M storage buildout was recently scrapped in favor of ranking the contents of the collection to see what works were best suited for deaccession. SFMoMA will sell a Rothko at Sotheby’s to fund acquisitions that would fill diversity gaps in its collection.[8] MoMA, meanwhile, has been subtlety deaccessioning works to pay for fresh acquisitions for decades.[9] Though deaccession is thorny due to regulations and the risk of alienating donors or their families, managed properly it allows museums to be able to reevaluate their works not as liabilities, but as assets that can be capitalized.

Scandals like the Sackler Family Foundation’s involvement in the opioid crisis, BP’s patronage after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, or the Louvre Abu Dhabi after abusive labor conditions were discovered on the museum’s construction site all reinforce the argument that “art is compromised when the funds that support it are unethical.”[10] The difference is that now digital media more than ever amplifying audiences’ challenges to institutions to do better. They demand that museums commit to their responsibility as stewards of public interest in a way that not only ensures the quality of programming as well as the source of funds that makes it possible.

Given the collective difficulties that arts institutions are facing, there is urgent pressure to continue exploring alternative funding models. It is quite possible therefore that we are on the verge of a new era of institutional fiduciary responsibility which will be pioneered by innovation born from the necessity to try concepts that for previous generations may have been unimaginable or technologically impossible. At Artemundi we welcome these new perspectives in creative sustainability like The Museum Fund.

[1] “ROI on Fundraising: The Trends. DataArts.” DataArts, culturaldata.org/the-fundraising-report/return-on-fundraising-index/trends/.

[2] Keener, Katherine. “Tate and Guggenheim Vow to Refuse Sackler Money.” Art Critique, 25 Mar. 2019, www.art-critique.com/en/2019/03/tate-and-guggenheim-vow-to-refuse-sackler-money/.

[3] Boseley, Sarah. “Tobacco Ads and Sports Sponsorship to Disappear.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 18 June 1999, www.theguardian.com/uk/1999/jun/18/sarahboseley1.

[4] Stromberg, Matt. “Main Museums Mysterious Closure Serves as a Cautionary Tale about Funding.” The Art Newspaper, 16 Feb. 2019, www.theartnewspaper.com/news/main-museum-s-mysterious-closure-serves-as-a-cautionary-tale.

[5] Small, Zachary. “$2.8 Million in Met Museum Admission Revenues Will Go to 175 Cultural Nonprofits.” Hyperallergic, 20 Mar. 2019, hyperallergic.com/490761/met-museum-175-nonprofits/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=WR 032219 – National Portrait&utm_content=WR 032219 – National Portrait CID_e635ca9eaaf5ee1fa9b9d32f5e4462da&utm_source=HyperallergicNewsletter&utm_term=28 Million in Met Museum Admission Revenues Will Go to 175 Cultural Nonprofits.

[6] Freeman, Nate. “How LACMA Is Taking Major Steps to Expand into China.” Artsy, 25 Mar. 2019, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-michael-govan-lacmas-major-expansion-china?utm_medium=email&utm_source=16382497-newsletter-editorial-daily-03-25-19&utm_campaign=editorial&utm_content=st-A.

[7] Pogrebin, Robin. “Clean House to Survive? Museums Confront Their Crowded Basements.” The New York Times, 10 Mar. 2019, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/10/arts/museum-art-quiz.html.

[8] Kinsella, Eileen. “SFMOMA Is Selling a Painting by Mark Rothko at Sotheby’s This Spring, and It Could Fetch Up to $50 Million.” Artnet News, 15 Feb. 2019, news.artnet.com/market/sothebys-sell-mark-rothko-sfmoma-spring-auctions-1466485.

[9] McClellan, Andrew. “Why Deaccessioning Isnt Always Bad News.” Apollo Magazine, 16 Mar. 2019, www.apollo-magazine.com/modern-art-museums-deaccessioning/.

[10] Spence, Rachel. “Who Funds the Arts and Why We Should Care.” Financial Times, 19 Sept. 2014, www.ft.com/content/4313691c-3513-11e4-aa47-00144feabdc0.